Navigating through a Carpet-Map

Yesterday, I attended the Maps workshop at the “Inspired Discipline” symposium organised by mLAB located in the Institute of Geography at the University of Bern. The workshop was led by Philippe Rekacewicz, who is an experimental cartographer, information designer and geographer. During the workshop, he answered a question about his personal journey as a cartographer. He told us about all the turns his life took because he did not settle to do maps as expected. Challenging the map is now considered as one of the permanent items of critical geography courses. Still, not much is written about the trouble critical cartographers had to go through to challenge customary ways of map-making. The map is a world-view, and changing the map means confronting established ways of seeing the world. The backlash against Arno Peters’ world map in 1974 left him “disappointed and shocked,” as his only intention was to depict a realistic picture of the actual size of the countries and continents. These complexities were also reflected in Rekacewicz’ introductory presentation showing us examples of critical map making (I especially loved the border walls) while emphasising:

The map is an intellectual construction.

The map is subjective.

The map is a tool of power.

At the practical part of the workshop, we were assigned to draw an identity map. In addition to a guide to map making, Rekacewicz asked us to draw the first thing coming to our minds when thinking about mapping our identities. He showed us some pictures from the book, “Images de pensée,” a collection of sketched designs, rough diagrams and meticulous plans. The book expresses “a thought at its moment of birth” with drawings from Darwin, Freud, Descartes, Goethe, Klee, Nabokov, etc. We were asked to work with these “thought-pictures.”

In the absurdity of sitting in a zoom call with 44 other people looking into the privacy of their homes without knowing them or their stories, I started to think: What would be the thing that I hold in my hands, show total strangers and say: Here! This is who I am! This is who I was! This is who I have become! And this might be the path to my future. How can I show movement in a map full of borders? How could I articulate the pain of immigration and the joy of taking in new smells and landscapes beyond my senses? How could I demonstrate the idea of belonging breaking into a thousand pieces every time I packed and moved back and forth between countries? How could I show the possibility of being everywhere and nowhere?

Suddenly, I started to draw my grandmother’s cooker. Maybe because I recently have read Rachel Roddy’s “a life in Cookers”, depicting in detail every single cooker she has experienced in her life: an object present in intimate memories of a future chef. I began to see my grandmother, hovering over her old gas cooker, humming an old Azeri song, frying onions and meat. Her curvy back and massive hands. Her hand-woven wool jacket. Her ancient pots and pans. Her china pot of tea brewing fresh black tea sitting at the top of her samovar (How could she drink so much tea?). The cooker was placed at a carving in the wall. She once told me that it was the fireplace before until one day grandpa came home with a shiny gas cooker. Her kitchen started to modernise, but she never adapted to the new ways of life. Her old-school generosity remained unchanged, as well as her ideas about life and a woman’s place in it. She remained a conservative, but her good heart always won the battle: she never closed her doors to her trouble-making granddaughter, who was holding a match in her hands to burn everything old and rusty. Even when the granddaughter was too radical for most intellectuals, grandma accepted God’s plan, cooking this rebellious child her favourite food without asking too many questions.

I remembered watching grandma from below as a child. Playing on the carpet with my toys. Watching her swirl around the kitchen, moving between the basin and the cooker. If her knees allowed, we would eat on a spread sitting on the carpet. The carpet was my playground, table, forbidden garden, bed, and sandbox. I walked in between colourful flowers, drove my toy cars along its lines, drank from the fountain, watched the birds, lions, and camels. I followed the caravan to far far countries. The carpet was my atlas, letting me imagine new territories in the security of having my grandma looking over me. Or sitting next to me with a pile of herbs or vegetables that needed to be prepared for winter.

There was a war going on. The border was not to pass; it was to be defended. The TV had only two channels and all the girls had the same haircut. The carpet was a sanctuary from an ugly world of reality. It was a map of unimaginable. It was a reminder of beauty.

Carpets are woven by women in Iran. Every knot is a story. Every knot holds history. Every knot is a point on a map. Iranians can look at a carpet and know where it comes from. Experts can even guess the village. From each flower’s twist, you can tell if the weaver is daydreaming or is weaving according to a carpet-map. If the carpet is asymmetrical you might know that there might be a crying new-born on the weaver’s back, tears for a brother killed in the war on her cheeks. If you listen carefully, you can hear her sighs for her husband, bringing a younger bride to the house. You can hear her singing: lullabies, songs about her life, or singing the carpet-map aloud for the co-weavers.

Naqshe Khani or pattern singing, is an audio guide to creating a carpet. The lead singer sings the colours and their placement, adding sympathetic verses for tired and over-worked women, singing her wishes, regrets and joys. Pattern singing is the accompanying song to the rhythmic music of weaving. Listen here:

“Naqshe” in Farsi means a map, but it also implies motif/pattern. Translating Naqshe Khani to pattern singing does not reflect the fact that each carpet actually has a map. These maps used to be expensive artefacts, hand-drawn and hand-painted with intricate colour combinations. Combined with experienced weavers’ skills, the map is a guide to create a carpet out of a pile of wool. Look here:

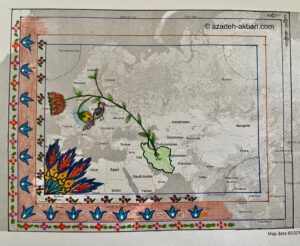

I would have loved to draw my identity map on graph paper, but I was not prepared for the rush of memories. I printed the Middle-East and Europe map and drew a carpet on the grey background of borders and countries. With two roots in Iran and Azerbaijan, a flower grows with branches in Sweden, England and Germany. The flower does not have roots in these places, but it blooms. In Sweden, there is only a leaf: a curiosity, the first smell of freedom, looking at the “others”. In England, it blooms to a peony, discovering new things, exploring her beauty, withering away as she confusingly looks for “home”. In Germany, she withdraws to become a blossom again, learning from scratch. A bird is sitting next to her. A blossom and a bird: the eternal sign of lovers in Persian poetry. She has fallen in love.

The carpet is unfinished. She is still growing.

The Persian carpet, the solid column of Iranian identity, the object of national pride, the woven power of women against their oppression, and the grounds of our collective imagination is also growing with us. Looking for videos for this piece, I found a digital gadget that reads the patterns for weavers. The robotic sound is like background music to the landscape of cheap carpets with stolen designs at IKEA. Its ugly and low-cost finishing is a reminder of a nation on its knees under international sanctions, ruled by corrupt men of God, getting poorer and poorer, selling her garden of dreams to the highest bidder.

One of my favourite artistic projects is Nazgol Ansarinia‘s Rhyme and Reason, transforming the Persian carpet’s traditional floral motifs into scenes of contemporary life in Iran. A family riding a motorcycle in the traffic of flowers and blossoms, men fighting at a curve of a branch with a policeman standing by, women covered in their hijab talking to each other. The carpet magically manages to communicate Tehran, the artist’s hometown: traffic, fights, smell of gasoline, strolls, sharing, fear, poverty, heritage, and maybe our national struggle to locate our identity.

__________

P.S. If you are interested in knowing more about Naqshe Khani, please refer to Mehdi Ahmadian‘s beautiful documentary at the Austrian Academy of Sciences and Golriz Shayani’s PhD project in Ethnomusicology at the University of Texas at Austin.